What is Lung Cancer ?

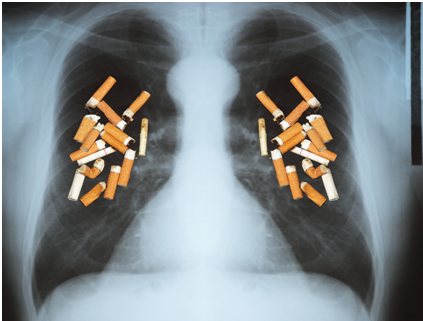

Lung cancer is a serious health problem that affects many people and their families. Cigarette smoke causes most lung cancers, but there are many other factors related to occupation, home, and family that increase the risk for lung cancer.

When a person develops lung cancer, tests are done to determine the type of lung cancer and if it has spread. When a cancer spreads, this is called metastasis. The size of the tumor and whether or not it is found in lymph nodes or other places in the body is measured on a scale called the cancer stage. The stage is an important feature used to help choose the best treatments.

Risk factors for lung cancer:

Smoking — Cigarette smoking is the most common risk factor for lung cancer. As an example, smoking is estimated to cause 80 to 85 percent of all lung cancers in the United States. A smoker's risk of developing lung cancer is 10 to 30 times greater than that of a nonsmoker. All forms of tobacco and smoking, including pipes, cigars, and chewing tobacco, may cause cancers of the mouth, throat, and lungs.

The risk of lung cancer increases with the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years of smoking. The quantity of cigarette smoking is usually summarized by the number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years smoked. For example, a person who smoked one pack per day for 20 years would be said to have 20 pack-years of smoking exposure.Quitting smoking can reduce the risk for lung cancer regardless of how many years a person has smoked. The risk of cancer remains high for several years after quitting smoking, but the risk does go down within 5 to 10 years after quitting. A former smoker's risk of lung cancer is never as low as a nonsmoker's risk. Secondhand smoke — Secondhand smoke, sometimes called passive smoking or sidestream smoke, can be hazardous to adults and children. Secondhand smoke contains the same toxic substances as directly inhaled smoke. Secondhand smoke is an important cause of both lung cancer and heart disease deaths. Secondhand smoke is also a risk factor for respiratory problems such as bronchitis, sinus problems, and ear infections in both adults and children.

Lung cancer symptoms

Most people with lung cancer have one or more symptoms. However, the symptoms of lung cancer may be the same as symptoms of other more common problems. If you are concerned about your symptoms, talk to your doctor or nurse.

The most common symptoms of lung cancer include:

- Cough – Lung cancer can cause a new cough or a change in a chronic cough. This is called hemoptysis, and this requires medical evaluation if it occurs.

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing, a whistling sound when you breathe

- Chest pain can develop and may be dull, sharp, or stabbing

- Voice hoarseness

- Headache and swelling of the face, arms, or neck

- Arm, shoulder, and neck pain can be caused by a tumor in the top of the lungs (called a Pancoast tumor). Other symptoms can include weakening of the hand muscles (due to pressure on the nerve that stimulates the arm), a droopy eyelid, and blurred vision.

Initial testing and diagnosis

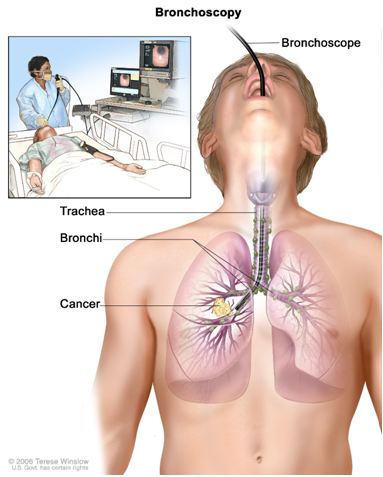

If you have symptoms that suggest lung cancer, your doctor will perform an examination. If your findings are still concerning, more tests, including blood work and x-rays or scans will then be ordered. If the chest x-ray or computed tomography (CT) scan shows an abnormal growth that could be a tumor, additional testing is performed to make a diagnosis. Usually, a small piece will need to be removed from the chest and examined with a microscope. This procedure is called a biopsy. Importantly, the decision to perform a biopsy does not mean that cancer is present. Biopsies are routinely performed to check for both cancer as well as many other diseases.

A biopsy can be done in one of several ways:

- Bronchoscopy is a procedure where a flexible tube with a camera and other small instruments is inserted through your mouth or nose and then into the windpipe (called the trachea). This procedure is described in detail separately

- Endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopy or EBUS is a technique that combines flexible bronchoscopy with ultrasound to first see lymph nodes in the chest and then to take biopsies from enlarged lymph nodes.

- CT-guided fine needle biopsy is performed by locating the tumor with a CT scan and inserting a thin needle through the skin to remove a tiny sample of tissue.

- Needle aspiration is performed by inserting a needle into lumps or lymph nodes that can be felt under the skin or seen with an ultrasound.

- Thoracentesis is insertion of a needle and small catheter into fluid collections in the chest to remove the fluid and look at it with a microscope.

- Surgery may be needed to remove the tumor entirely if it is small or if other biopsy procedures have not made a definitive diagnosis.

Advanced testing in lung cancer

In addition to looking at the tumor with a microscope, some lung cancers may also be tested for abnormal proteins called biomarkers or for mutations in their DNA. If present, these biomarkers or genetic mutations may be used to determine the best treatment options. Common biomarkers in lung cancer include EGFR mutations, ALK translocations, and ROS1 translocations. This is a rapidly changing area of lung cancer research, and the list of biomarkers and targeted treatment options is rapidly changing.

Types of lung cancer

There are many different kinds of lung cancer based on how they look under a microscope. However, there are two main categories used to determine the best treatment approach:

- Small cell lung cancer is found in about 10 to 15 percent of patients.

- Non-small cell lung cancer (often abbreviated NSCLC) includes most other types of lung cancer and is found in the remaining 85 to 90 percent of patients. There are subcategories of NSCLC, the most common of which are adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma.

The reason that small cell cancer is separated from non-small cell cancers is that small cell cancers grow and metastasize differently. Small cell cancer tends to be more aggressive and can spread quickly. Small and non-small cancers have different treatment regimens for surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Staging of lung cancer

Once lung cancer is diagnosed, the next step is to carefully measure the size of the tumor, determine its exact location, and look for evidence that it has spread. This process is called staging. Determining the stage of a lung cancer can be complicated because many different tests and procedures are used when determining the stage. The factors used to assign stage to non-small cell cancer are:

- The size and location of the tumor

- Whether the tumor has invaded lymph nodes and tissues inside the chest

- Whether the tumor has spread to places outside the chest (for example, lung cancer can spread [metastasize] to places like the bones, liver, adrenal glands, or elsewhere)

Non-small cell lung cancer stages range from I to IV. In general, the lower numbers (stages I and II) suggest that the tumor is smaller and has not spread far. By comparison, the higher numbers (stage III and IV) suggest that the tumor is larger or has metastasized.In general, lower-stage cancers require different kinds of treatment than do higher-stage cancers. Furthermore, the overall health, goals, and preferences of the lung cancer patient are very important in determining the best treatment options. Early-stage lung cancers are generally managed with surgery to remove the tumor and surrounding lung. However, patients who cannot have surgery or who prefer not to have surgery may be treated with focused radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. Stage III lung cancers are usually not treated with surgery, and the treatment options for patients with these tumors include chemotherapy and radiation therapy in combination. When the cancer has spread outside of the chest (stage IV), chemotherapy, targeted radiation therapy, and other treatments to minimize pain or anxiety may have a role in controlling the disease and its symptoms. All patients should consider goals of care and what quality of life means to them. Alternative treatment approaches for patients with advanced-stage cancer include palliative care and treatments designed to control symptoms. These approaches may improve quality of life and often achieve good survival times and acceptable quality of life

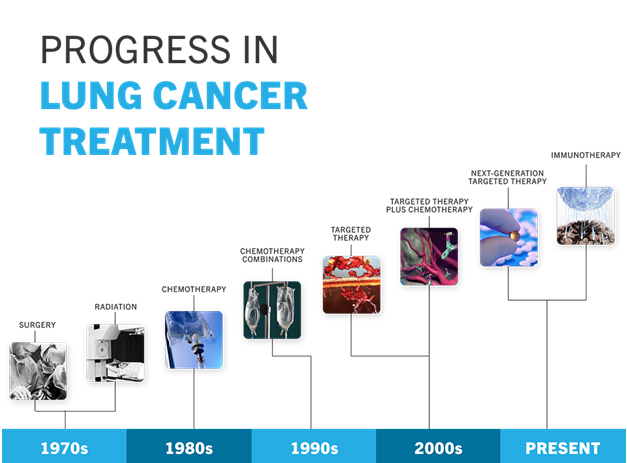

Treatment of lung cancer

Stage I and II: Whenever possible, surgery is recommended as the first treatment in people with stage I or II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Radiation therapy may be recommended for people who are not good candidates for surgery due to severe lung disease or other underlying medical problems. In some cases, the initial surgery or radiation therapy may be followed by adjuvant (after surgery) chemotherapy.

Surgery — Surgery to remove the cancer is the preferred treatment for stage I and stage II NSCLC. Options for surgery include the following, depending upon the size and position of the tumor in the chest:

- Lobectomy – This is the removal of one lobe (section) of the lung. (Normally the right lung has three lobes, and the left lung has two.)

- Segmentectomy or wedge resection – Both of these procedures involve removing part of the lung but not an entire lobe. They may be considered in some patients with a small tumor of 2 cm or smaller. This form of surgery may also be preferred for some people who could not tolerate conventional lobectomy, for example, in the case of a person whose lungs do not work well.

- Pneumonectomy – This is the removal of the entire affected lung. It is sometimes necessary in cases where lobectomy cannot completely remove the tumor, as is often the case for a primary tumor near the middle of the chest. Pneumonectomy requires that the remaining lung be relatively healthy. Radiation therapy — Radiation therapy involves the use of X-rays to destroy cancer cells. Radiation therapy may be recommended for people with stage I or II NSCLC in the following situations:

- After surgery, radiation therapy may be recommended for patients with tumor left behind at the margins (edges) of the surgical resection, or for patients felt to have a high risk for locoregional (nearby) recurrence. It is not a clear standard therapy, and it is not indicated in patients with no lymph node involvement who have negative surgical margins (no evidence of cancer at the margins), with some evidence suggesting that it can have a net harmful effect in such patients.

- Radiation therapy may be used, alone or with chemotherapy, in people who are unable to tolerate or do not want surgery.

- Radiation treatments are brief and not painful, similar to having an X-ray. Treatments are usually done five days per week for several weeks.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy — Chemotherapy is a treatment given to slow or stop the growth of cancer cells. Even after a cancer has been removed with surgery, cancer cells can remain in the body, increasing the risk of a relapse.

Chemotherapy can get rid of these cancer cells and increase the chance of cure, but it is indicated only in patients with a high enough risk of recurrence to justify the side effects of chemotherapy. Chemotherapy in the postoperative setting (after surgery) is called adjuvant therapy, meaning "helper." It is recommended for people with stage II or III NSCLC, and for some (but not all) people with stage I disease, as it is generally not recommended for patients with node-negative cancers that measure 4 cm in diameter or smaller. Chemotherapy is not given every day but instead is given in cycles. A cycle of chemotherapy, which is typically 21 or 28 days, refers to the time it takes to give the treatment and then allow the body to recover from the side effects of the medicines. Most treatments involve a combination of two chemotherapy drugs (called a doublet chemotherapy regimen). The best studied options include the agent cisplatin, though the potential for challenging side effects may make it a less ideal choice than the related drug carboplatin for some patients. Most of the drugs are given into a vein (intravenous or "IV"). Typically, adjuvant treatment regimens for NSCLC last about three months.

Stage IV lung cancer

Targeted therapy: Targeted therapy is the name for anticancer treatments that interfere with how a cancer grows and spreads when a very specific abnormality is present. These treatments work in a different way than standard chemotherapy.

The decision about which targeted therapy, if any, to use depends on your particular cancer. Generally, a sample of your tumor that was obtained by surgery or biopsy is analyzed in the laboratory to make this decision. When such an abnormality is present, the likelihood of a favorable response to treatment is much higher than with older forms of treatment such as chemotherapy.

Testing can be done to see if your cancer belongs to one of the categories that is likely to respond to targeted therapy.

- Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations – When the epidermal growth factor receptor contains a particular abnormality (mutation), this change can stimulate growth and spread of the tumor. Erlotinib (Tarceva), gefitinib (Iressa), and afatinib are targeted chemotherapy medicines that block the growth of the tumor in this situation. If an abnormality in EGFR is found, targeted therapy is generally used instead of standard chemotherapy. The most common side effects of erlotinib and gefitinib are skin rash and diarrhea.

- Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene abnormalities – A fusion (combination) of the ALK gene with another gene such as EML can drive the growth of some non-small cell lung cancers. Crizotinib is a targeted medicine that blocks the cancer stimulus caused by this ALK abnormality. Crizotinib is more effective than standard chemotherapy in patients with lung cancer containing this abnormality, and thus crizotinib is generally recommended as the initial therapy instead of standard chemotherapy in this situation. Crizotinib is generally well tolerated, and the most common side effects of crizotinib are mild changes in vision and nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

If your initial treatment with a targeted agent does not work, or if you initially respond and then your disease progresses, your doctor may recommend treatment with chemotherapy.

- Chemotherapy: Most treatments involve a combination of two chemotherapy drugs. The most commonly used regimens include either cisplatin or carboplatin ; this is combined with one of several other drugs (such as pemetrexed [Alimta], paclitaxel [Taxol], docetaxel, gemcitabine , vinorelbine.

- Most of the drugs are given into a vein (intravenous, IV) once every three weeks. In some cases, your doctor will recommend combining these chemotherapy drugs with bevacizumab (Avastin), a medicine that blocks a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Four to six cycles of chemotherapy are usually recommended, depending upon your response to treatment. In many cases, your doctor may recommend continuation of treatment with one drug after the four cycles of chemotherapy if you have had a favorable response to the initial treatment.